There has been plenty of talk lately about threadpool starvation in .NET:

- https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/vancem/2018/10/16/diagnosing-net-core-threadpool-starvation-with-perfview-why-my-service-is-not-saturating-all-cores-or-seems-to-stall

- https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/vsoservice/?p=17665

- or even on our own blog: https://labs.criteo.com/2018/09/monitor-finalizers-contention-and-threads-in-your-application/

What is it about? This is one of the numerous ways asynchronous code can break if you wait synchronously on a task.

To illustrate that, consider a web server that would execute this code:

You start an asynchronous operation (DoSomethingAsync) then block the current thread. At some point, the asynchronous operation will need a thread to finish executing, so it’ll ask the threadpool for a new one. You end up using two threads for an operation that could be done with just one: one waiting actively on the Wait() method call and another one performing the continuation. In most cases this is fine. But it can become a problem if you deal with a burst of requests:

- Request 1 arrives to the server. ProcessRequest is called from a threadpool thread. It starts the asynchronous operation then waits on it

- Requests 2, 3, 4, and 5 arrive to the server

- The asynchronous operation completes and its continuation is enqueued to the threadpool

- In the meantime, since 4 requests have arrived, 4 calls to ProcessRequest have been enqueued before your continuation

- Each of those requests will in turn start an asynchronous operation and block their threadpool thread

Combined with the fact that the threadpool grows very slowly (one thread per second or so), it’s easy to understand how a burst of requests can push a system into a situation of thread starvation. But there’s something missing in the picture: while the burst could temporarily lock the system, unless the workload is continuously increasing, the threadpool should be capable of growing enough to eventually recover.

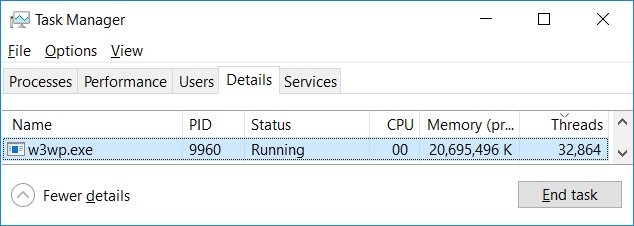

Yet, it does not fit what we observed on our own servers. We usually restart our instances as soon as a starvation happens, but in one case we didn’t. The threadpool grew until its hardcoded limit (32767 threads), and the system never recovered:

If you do the math, 32767 threads should be more than enough to handle the 1000-2000 QPS that our servers process, even if every request required 10 threads!

It seems there’s something else going on.

The part where things get worse

Let’s consider the following code. Take a minute to guess what will happen:

Producer enqueues 5 calls to Process every second. In Process, we yield to avoid blocking the caller, then we start a task that will wait 1 second and wait for it. In total, we start 5 tasks per second and each of those tasks will need an additional task. So we need 10 threads to absorb the constant workload. The threadpool is manually configured to start with 8 threads, so we are 2 threads short. My expectations are that the program will struggle for 2 seconds until the threadpool grows to absorb the workload. Then it needs to grow a bit further to process the additional workitems that we enqueued during the 2 seconds. After a few seconds, the situation will stabilize.

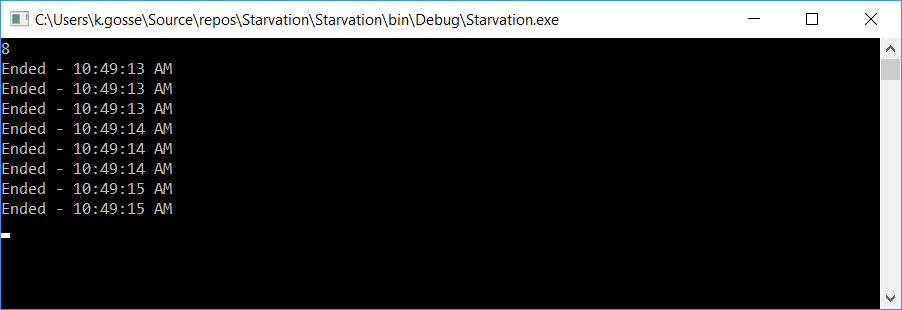

But if you run the program, you’ll see that it managed to display “Ended” a few times in the console, then nothing happens anymore:

Note that this code assumes that Environment.ProcessorCount is lower or equal to 8 on your machine. If it’s bigger, then the threadpool will start with more thread available, and you need to lower the delay of the Thread.Sleep in Producer() to set the same conditions.

Looking at the task manager, we can see that CPU usage is 0 and the number of threads is growing at about one per second:

Here I’ve let it run for a while and got to a whopping 989 threads, yet still nothing is happening! Even though 10 threads should be enough to handle the workload. So what’s going on?

Every bit is important in that code. For instance, if we remove Task.Yield and manually start new tasks instead in Producer (the comments indicate the changes):

Then we get the predicted behavior! The application struggles a bit at first, until the threadpool grows enough. Then we have a steady stream of messages, and the number of threads is stable (29 in my case).

What if we take that working code but start Producer in its own thread?

This frees one thread from the threadpool, so we should expect it to work slightly better. Yet, we end up with the first case: the application displays a few messages before locking up, and the number of threads grows indefinitely.

Let’s put Producer back to a threadpool thread, but use the PreferFairness flag when starting the Process tasks:

Then once again we end up with the first situation: the application locks up, and the number of threads increases indefinitely.

So, what is really going on?

The threadpool queuing algorithm

To understand what’s happening, we need to dig into the internals of the threadpool. More specifically, into the way the workitems are queued.

There are a few articles out there explaining how the threadpool queuing works (http://www.danielmoth.com/Blog/New-And-Improved-CLR-4-Thread-Pool-Engine.aspx). In a nutshell, the important part is that the threadpool has multiple queues. For N threads in the threadpool, there are N+1 queues: one local queue for each thread, and one global queue. The rules for picking in which queue your item will go are simple:

- The item will be enqueued to the global queue:

- if the thread that enqueues the item is not a threadpool thread

- if it uses ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem/ThreadPool.UnsafeQueueUserWorkItem

- if it uses Task.Factory.StartNew with the TaskCreationOptions.PreferFairness flag

- if it uses Task.Yield on the default task scheduler

- In pretty much all other cases, the item will be enqueued to the thread’s local queue

How are the items dequeued? Whenever a threadpool thread is free, it will start looking into its local queue, and dequeue items in LIFO order. If the local queue is empty, then the thread will look into the global queue and dequeue in FIFO order. If the global queue is also empty, then the thread will look into the local queues of other threads and dequeue in FIFO order (to reduce the contention with the owner of the queue, which dequeues in LIFO order).

How does that impact us? Let’s go back to our faulty code.

In all the variations of the code, the Thread.Sleep(1000) is enqueued in a local queue, because Process is always executed in a threadpool thread. But in some cases we enqueue Process in the global queue and in others in the local queues:

- In the first version of the code, we use Task.Yield, which queues to the global queue

- In the second version, we use Task.Factory.StartNew, which queues to the local queue

- In the third version, we change the Producer thread to not use the threadpool, so Task.Factory.StartNew enqueues to the global queue

- In the fourth version, Producer is a threadpool thread again but we use TaskCreationOptions.PreferFairness when enqueuing Process, thus using the global queue again

We can see that the only version that worked was the one not using the global queue. From there, it’s just a matter of connecting the dots:

- Initial condition: we put our system in a state where the threadpool is starved (i.e. all the threads are busy)

- We enqueue 5 items per second into the global queue

- Each of those items, when executing, enqueues another item into the local queue and waits for it

- When a new thread is spawned by the threadpool, that thread will first look into its own local queue which is empty (since it’s newborn). Then it’ll pick an item from the global queue

- Since we enqueue into the global queue faster than the threadpool grows (5 items per second versus 1 thread per second), it’s completely impossible for the system to recover. Because of the priority induced by the usage of the global queue, the more threads we add, the more pressure we put on the system

When using the local queue instead (second version of the code), the newborn threads will pick items from the other threads’ local queues since the global queue is empty. Therefore, new threads helps alleviate the pressure on the system.

How does it translate to a real-world scenario?

Take the case of an HTTP-based service. The HTTP stack, whether it uses Windows’ http.sys or another API, is most likely native. When it forwards new requests to the .NET user code, it’ll queue them in the threadpool. Those items will necessarily end up in the global queue, since the native HTTP stack can’t possibly use .NET threadpool threads. Then the user code relies on async/await, and very likely use the local queues all the way. It means that in a situation of starvation, new threads spawned by the threadpool will process the new requests (enqueued in the global queue by the native code) rather than completing the ones already in the pipe (enqueued in the local queues). Therefore, we end up in the situation previously described where every new thread adds even more pressure to the system.

Another situation where things can turn ugly is if the blocking code is running as part of the callback of a timer. Timer callbacks are enqueued into the global queue. I believe such a case can be found here (pay a close attention to the TimerQueueTimer.Fire call at the beginning of the callstack for the 1202 threads shown): https://blogs.msdn.microsoft.com/vsoservice/?p=17665.

What can we do about that?

From a user-code perspective, unfortunately not much. Of course, in an ideal world we would use non-blocking code and never end up in a threadpool starvation situation. Using a dedicated pool of threads around the blocking calls can help a lot, as you stop competing with the global queue for new threads. Having a back-pressure system is a good idea too. At Criteo we’re experimenting with a back-pressure system that measures how long it takes for the threadpool to dequeue an item from a local queue. If it takes longer than a few configured threshold, then we stop processing incoming requests until the system recovers. So far it shows promising results.

From a BCL perspective, I believe we should treat the global queue as just another local queue. I can’t really see a reason why it should be treated in priority compared to all other local queues. If we’re afraid that the global queue would grow quicker than the other queues, we could put a weight on the random selection of the queue. It would probably require some adjustments, but this is worth exploring.

Post written by:

|

Christophe Nasarre Staff Software Engineer, R&D. Twitter: chnasarre |

Kevin Gosse Staff Software Engineer, R&D. Twitter: KooKiz |

-

CriteoLabs

Our lovely Community Manager / Event Manager is updating you about what's happening at Criteo Labs.

See DevOps Engineer roles